About Bloody Monday

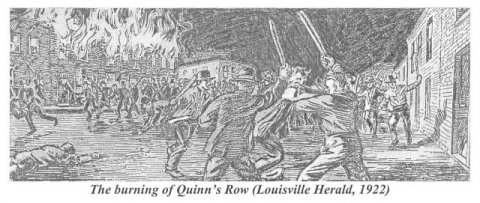

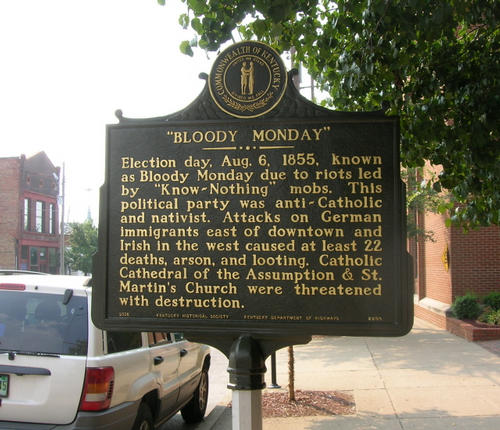

In the mid 1800’s, the American Nativists (also known as “Know Nothings”) were convinced that the newly arrived (mostly Irish and German and other Catholic immigrants would undermine the American way of life. In cities across this country, there was unrest: it was a time of great change and uncertainty, fear, violence, slavery, and prejudice (“No Irish Need Apply”)… and rioting. Louisville’s “Bloody Monday” election day rioting in August 1855 was certainly among the most violent outbreaks, with 22 confirmed deaths (though there is reason to believe that the real number was greater). In 1995, then-AOH president Paul Whitty applied for a Bloody Monday historic marker to be placed between 10th and 11th Streets on West Main, the site of the burning of a row of frame houses owned by an Irishman, Patrick Quinn. (The street was barricaded and the buildings burned… several were shot while trying to escape the flames, including Mr. Quinn, who was subsequently thrown back into the fire.) In 2006, after the 150th anniversary memorial events, the AOH and German-American Club raised the funds to erect the marker and took part in its unveiling on August 5, 2006. Those assembled then proceeded to Nelligan Hall (2010 Portland Ave) in the historically-Irish and nearby Portland neighborhood… Irish and German food and entertainment were available for purchase.

Unveiled on Saturday, August 4, 2006

Kentucky Historical Highway

Marker #2205

Marker #2205

The Back of the Marker reads:

AMERICAN (KNOW-NOTHING) PARTY

This party feared that Catholic immigrants from Germany and Ireland threatened Protestantism and democracy. By 1854, the party claimed a million members nationwide and led Jefferson Co. govt. They split over slavery and by the end of the Civil War they had vanished from politics in Louisville and Jefferson Co. Given by Anc. Ord. Hibernians & German-Amer. Club

Location: 1011 West Main Street, Louisville, Kentucky

This marker was unveiled 151 years after the event… thanks to the efforts of Paul Whitty, Esq. who submitted the wording to the state historic landmark board and to the German American Club and the AOH for funding this marker. It can be found between 10th and 11th Streets on West Main Street in front of the Ky Lottery Corporation.

For Those Who Perished in the Riots of Bloody Monday

He fled his home,

Across the land

To the Irish Sea,

He lost his mom,

father, friends and generations three.

So he set asail,

Across the water,

To a place of food and free,

The hopes of dreams,

Did trust the breeze,

The sights that did unfold,

New Orleans port

He found himself.

Up the Mississippi River

He toiled away,

Kentucky lore attracted him,

And that’s where he stayed.

The water so blued,

And the fields so green,

His life there he made,

And time flew by.

Things were grand,

The pain behind was gone,

He took a bride,

And made a life.

He never could conceive,

That things would change,

So drastically,

Until the famous day,

of Prentice boys,

Who knew nothing.

His mind went back,

From where he’d come

And realized then,

That he had not escaped

The horrors of Ireland.

As the fires did rage,

He only surmised,

It’s time and he passed away.

– A.J. Brian

From 1855… (150th Anniversary Article from 2006 is below)

Bloody Monday – Louisville Daily Journal – August 7, 1855

(Courtesy of Janis Fowler)

THE ELECTION RIOTS.

BLOODY WORK.

MURDER AND ARSON. TWENTY MEN KILLED.

We passed yesterday through the forms of an election. As provided for by statute, the polls were opened, and privilege granted to such as were “right upon the goose,” with a few exceptions, to exercise their election franchise. Never, perhaps, was a greater farce, or as we should term it, tragedy, enacted. Hundreds and thousands were deterred from voting by direct acts of intimidation, others through fear of consequences, and a multitude form alack of proper facilities. the city, indeed, was, during the day, in possession of an armed mob, the base passions of which were infuriated to the highest pitch by the incendiary appeals of the newspaper organ and the popular leaders of the Know Nothing party.

On Sunday night, large detachments of men were sent to the First and Second Wards to see that the polls were properly opened. These men, the “American Executive Committee” supplied with the requisite refreshments, and and as may be imagined they were in very fit condition to see that the rights of freemen were respected. Indeed they discharged the important trusts committed to them in such manner as to commend them forever to the admiration of out-laws! They opened the polls; they provided ways and means for their own party to vote; they bluffed and bullied all those who could not show the sign; they in fact converted the election into a perfect farce, without one redeeming or qualifying phase.

We do not know when or how their plan of operations was devised. Indeed we do not care to know when such a system of outrage–such perfidy–such dastardly– was conceived. We only blush for Kentucky that her soil was the scene for such outrages, and that some of her sons were participants in the uefarious (sic) swindle.

It would be impossible to state when or how this riot commenced. By day break the polls were taken possession of by the American party, and in purauance (sic) of their preconcerted game, they used every stratagem or device to hinder the vote of every man who could not manifest to the “guardians of the polls” his soundness in the K. N. question. We were personally witness to the procedure of the party in certain wards, and of these we feel authorized to speak. At the Seventh Ward we discovered that for three hours in the outset in the morning it was impossible for those not “posted” to vote, without the greatest difficulty. In the Sixth Ward a party of bullies were masters of the polls. We saw two foreigners driven from the polls; forced to run a guantlet, beat unmercifully, stoned and stabbed. In the case of one fellow the Hon. Wm. Thomasson, formerly a member of Congress from this district, interfered, and while appealing to the maddened crowd to cease their acts of disorder and violence Mr. Thomasson was struck from behind and beat. His gray hairs, his long public service, his manly presence, and his thorough Ameribanism (sic), availed nothing with the crazed mob. Other and serious fights occurred in the Sixth Ward, of which we have no time to make mention now.

The more serious and disgraceful disturbances occurred in the upper wards. The vote cast was but but a partial one, and nearly altogether on one side. no show was given to the friends of Preston, who were largely in the majority, but who in the face of cannon, muskets and revolvers, could not, being an unarmed and quiet populace confront the mad mob. So the vote was cast one way, and the result stands before the public.

In the morning, as we state elsewhere, George Berg, a carpenter living on the corner of 9th and Market, was killed near Hancock street. A German named Fritz, formerly a partner in the Galt House, was severely, if not fatally beaten. In the afternoon a general row occurred on Shelby street, extending from Main to Broadway. We are unable to ascertain the facts concerning the disturbance. Some fourteen or fifteen men were shot, including Officer Williams, Joe Selvage and others. two or three were killed, and a number of houses, chiefly German coffee houses, broken into and pillaged. About 4 o’clock, when the vast crowd, augmented by accessions from every part of the city, and armed with shot-guns, muskets and rifles were proceeding to attack the Catholic church on Shelby street, Mayor Barbee arrested them with a speech, and the mob returned to the First Ward polls. Presently a large party with a piece of brass ordnance, followed by a number of men and boys with muskets. In an hour afterwards the large brewery on Jefferson street, near the junction of Green, was set fire to.

In the lower part of the city, the disturbances were characterized by a greater degree of bloody work. Late in the afternoon three Irishmen going down Main street, near Eleventh, were attacked, and one knocked down. then ensued a terrible scene, the Irish firing from the windows of their houses, on Main street, repeated volley’s. Mr. Rodes, a river-man, was shot and killed by one in the upper story, and a Mr. Graham met with a similar fate. An Irishman who discharged a pistol at the back of a man’s head was shot and then hung. He, however, survived both punishments. John Hudson, a carpenter, was shot dead during the fracas.

After dusk, a row of frame houses on Main street between Tenth and Eleventh, the property of Mr. Quinn, a well known Irishman, were set on fire. The flames extended across the street and twelve buildings were destroyed. These houses were chiefly tenanted by Irish, and upon any of the tenants venturing out to escape the flames, they were immediately shot down. No idea could be formed on the number killed. We are advised that five men were roasted to death, having been so badly wounded by gun shot wounds that they could not escape from the burning buildings.

Of all the enormities and outrages committed by the American party yesterday and last night, we have not time now to write. The mob having satisfied its appetite for blood, repaired to Third street, and until midnight made demonstrations against the “Times” and “Democrat” offices. the furious crowd satisfied itself, however, with breaking a few window panes, asd (sic) burning the sign of the Times office.

At one o’clock this morning a large fire is raging in the upper part of the city.

Upon the proceedings of yesterday and last night we have no time, nor heart now to comment. We are sickened with the very thought of the men murdered, and houses burned and pillaged, that signalized the American victory yesterday. Not less than twenty corpses from the trophies of the wonderful achievement.

Recalling Bloody Monday

Events to mark 1855 anti-immigrant riots in city

By Peter Smith

The Courier-Journal

Moving through the main streets of town, the Protestant mobs attacked and slaughtered immigrant Catholics — with ropes, guns, clubs and pitchforks.

At the end of what the Catholic bishop described as a daylong “reign of terror,” and what history would call Bloody Monday, at least 22 people were dead. And it happened in Louisville.

“You run into a lot of people who don’t even know what Bloody Monday was,” said Vicky Ullrich, a Louisville woman whose German-speaking Swiss ancestors fled to Indiana for safety after the events of that day — Aug. 6, 1855.

Yet, “given what the situation is today, with another influx of immigrants increasing the diversity of Louisville,” Ullrich said, it’s important that Bloody Monday be remembered “so that a similar event does not happen again.”

That’s why she’s helping to organize a series of commemorations next Saturday to mark the 150th anniversary of Bloody Monday, election-day riots in which Protestant mobs bullied immigrants away from polls and began rioting in Irish and German neighborhoods.

The anniversary events, sponsored by metro government and civic groups, will include a panel discussion and a bus tour of places connected to the riots.

Stories of atrocities from that day in 1855 abounded, such as of an elderly longtime citizen whose murdered body was thrown into the flames of his burning property. The victim’s only “crime,” lamented the Daily Democrat newspaper, was “that he was an Irishman and a Catholic.”

Though Protestants were among the dead, most victims were Catholics targeted by mobs who feared the immigrants’ growing numbers.

Irish and German immigrants, most of them Catholic, made up nearly a quarter of Louisville’s population of 43,000 at the time, according to the Encyclopedia of Louisville. Most native-born residents were Protestant.

Roy Fuller, who lectures on religion at the University of Louisville, said students today can scarcely believe the stories of Bloody Monday and similar anti-Catholic attacks of that era in other cities.

“We have grown up in an America where Catholics have been very visible and significant in terms of numbers,” he said. “It’s hard to imagine there would be attacks like this directed against Catholics.”

Students also are baffled by the propaganda of the day, which demonized Catholics as members of a sexually perverse, treasonous conspiracy that was secretly trying to turn America over to the pope.

“They’re even more surprised that people would believe such things,” Fuller said.

Promoting tolerance

Some have said the riots caused many immigrants to flee or avoid Louisville, sapping its economic strength and allowing St. Louis and Cincinnati to eclipse it.

While other historians disagree with that notion, many civic and religious leaders today say that Louisville has since gone out of its way to promote tolerance.

Present-day immigrants find Louisville “very welcoming and open to people from not only Germany and Ireland but also Somalia and Jordan and Mexico and Vietnam,” said Omar Ayyash, a native of Jordan and director of the Louisville Metro Office for International and Cultural Affairs. “It’s an unfortunate thing that human nature has to go to extreme hatred and bloodshed to learn that a society cannot flourish and grow” that way, he said.

Today, Louisville has three private agencies that bring refugees from troubled lands, and the city has gained national attention for such interfaith endeavors as its annual Festival of Faiths and its network of neighborhood community ministries.

“In contrast to times past, there is such a wonderful ecumenical environment,” said the Rev. Bill Hammer, head of the Office of Ecumenical and Interreligious Relations for the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Louisville.

While Protestants remain the city’s largest religious group, there now are about 157,000 Catholics — still nearly a quarter of the population.

Semsudin Haseljic, a case manager for Kentucky Refugee Ministries, said city officials and residents have welcomed immigrants and supported them during such recent incidents as when Muslims weathered harassment after the 2001 terrorist attacks.

“Outside of some events after 9/11, it’s been a smooth ride,” said Haseljic, a Muslim who came to Louisville 11 years ago as a refugee from the religious war in his native Bosnia.

The Rev. Clyde Crews, author of a history of the Archdiocese of Louisville, said that then-Louisville Bishop Martin Spalding and Protestant leaders began establishing this more tolerant environment immediately after Bloody Monday, when they called for calm rather than revenge.

Had the two sides taken a harder line, Louisville could have become “the Belfast of America,” said Crews, a Bellarmine University theology professor.

Editor’s ‘tarnished legacy’

But the ghost of Bloody Monday haunts the legacy of one prominent newspaper editor.

George Prentice, editor of the Louisville Daily Journal newspaper, a predecessor of The Courier-Journal, was widely accused of inflaming the mobs in editorials in the days before the riots. He denounced the “most pestilent influence of the foreign swarms” loyal to a pope he called “an inflated Italian despot who keeps people kissing his toes all day.”

Some say Prentice gets too much blame and that city officials created riot conditions with poorly policed, overcrowded voting precincts.

Periodic campaigns to remove Prentice’s statue from outside the Louisville Free Public Library downtown — which honors his other political and literary achievements — eventually resulted in the placing of a plaque describing his “tarnished legacy.”

Prentice’s “raw bigotry” is “part of the past that we have to live with, but I don’t think that’s our legacy,” said Courier-Journal Forum editor Keith Runyon, who edited a historical supplement on the newspaper’s 125th anniversary in 1993. The newspaper of 1855 “was about as far as you can get from The Courier-Journal of 2005,” Runyon said. “Editorially, we always have been concerned in modern times about minority rights, about assimilation, about fair treatment of immigrants.”

Bloody Monday has also left a burden for Louisville historians, who continue to wrestle with the sketchy, partisan accounts of it that appeared in the city’s newspapers and official records.

“We don’t argue about what happened in the earthquakes of 1811-12,” said historian and Metro Councilman Tom Owen. “We don’t argue about what happened in the 1937 flood or the tornado of 1890. But professionals debate both the causation and the result of Bloody Monday.”

Yet the important thing, he said, is not “who fired the first shot.”

What is crucial, he said, is to “resolve to never let the fires of passion, of fear or of hatred ever so overwhelm us that something like this would ever happen again.”